Tax the Rich, Save the World. It Is That Simple.

Patriotic Millionaires Founder and President Erica Payne called for increased taxes on the wealthy in a speech at a United Nations special meeting.

President Donald Trump claims to support a “fair” new framework for North American trade that puts American workers first. Understandably, this has sparked demands for a fairer distribution of the benefits of trade for workers in all three countries that are part of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

The Canadian government has apparently decided to call Trump’s bluff. During the recent second round of NAFTA talks in Mexico City, Canadian negotiators reportedly demanded that the United States roll back its right-to-work laws. Despite the misleading name, these laws actually discriminate against union activities that protect the rights of workers.

In right-to-work states, individual workers can refuse to pay union dues but still be entitled to union benefits and representation. The purpose is to bleed unions dry—and it works. Union coverage is much lower and income inequality higher in the 28 U.S. states with right-to-work laws.

Restricting U.S. right-to-work laws would certainly benefit North American workers. Canadian employers, including auto parts manufacturers and most notoriously Caterpillar in 2012, have relocated plants to right-to-work states. This ability of multinationals to shift production to low-wage, low-standards regions puts downward pressure on wages and working conditions throughout North America.

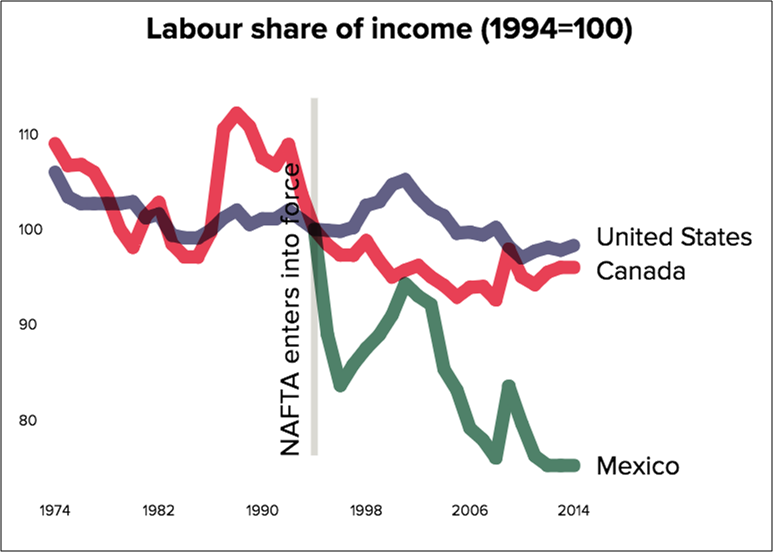

Since NAFTA went into effect in 1994, the labor share of income has fallen in all three NAFTA countries, but most drastically in Mexico, where labor’s take fell by a stunning 50%. Source: CCPA Monitor (September-October 2017).

There have been proposals to enact right-to-work laws in Canada (e.g., by the defeated Tim Hudak Conservatives in the last Ontario provincial election), but so far none have taken root. In fact, since the 1940s, Canadian labor laws have required all unionized employees to pay dues, while entitling even non-members to union representation.

The big question in the NAFTA talks is whether the Canadian government is serious about achieving meaningful progress on labor rights, or if such demands are simply tactical and will be watered down later in the talks.

It is hard to see the Trump administration agreeing to include restrictions on right-to-work in a revamped NAFTA. Even if it did, what are the chances a Republican-dominated Congress would let it pass? Trump endorsed right-to-work laws during the presidential campaign and some congressional Republicans have introduced a national right-to-work bill.

Even so, the Canadian proposal is a smart, positive move that puts the United States on the back foot and tests the sincerity of Trump’s pro-worker rhetoric. Hopefully, this opportunity for meaningful progress won’t be lost. It would not be hard to improve upon NAFTA’s abysmal labor protections, but that would be setting the bar far too low.

As the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA) emphasized in its brief on the NAFTA renegotiation, truly effective labor provisions must set high, fully enforceable standards. Workers and unions must be able to bring complaints directly to an independent authority that is obliged to investigate fully. There should be consequences, including high fines or trade sanctions, when employers or governments are found to violate

But it’s also important to recognize that, without changing NAFTA’s overall template, even a gold-plated labor chapter cannot counterbalance lopsided investment protections (such as investor-state dispute settlement, which allows private foreign investors to sue governments in international tribunals over certain actions that might reduce their profits), excessive intellectual property rights or regulatory “co-operation” mechanisms that erode protective standards and public interest regulations. Twenty-five years of NAFTA and similar corporate-biased trade deals have underlined that.

Suppression of basic labor rights and free trade have operated in concert to make NAFTA anything but “fair” for workers. While Trump might not embrace Canadian proposals to curtail right-to-work laws in NAFTA, and whether or not our government is truly committed to the idea, it is totally appropriate to be thinking along these lines as the negotiations move forward.

Originally published by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

by Erica Payne

Patriotic Millionaires Founder and President Erica Payne called for increased taxes on the wealthy in a speech at a United Nations special meeting.

by Jenny Ricks

We will win economic justice when people power becomes stronger than those driving and benefitting from the status quo.

by Manuel Pérez-Rocha

U.S. and Canadian civil society groups are denouncing their own governments’ efforts, driven by the agribusiness industry, to repeal Mexico’s proposed ban on genetically modified corn.

Inequality.org

→ In Your Inbox

Get the indispensable guide to the latest on our unequal world, in your inbox every Wednesday.

You can unsubscribe any time. We do not sell or share your information with others.

Click to close

Inequality.org

→ In Your Inbox

Get the indispensable guide to the latest on our unequal world, in your inbox every Wednesday.

You can unsubscribe any time. We do not sell or share your information with others.

Click to close

Inequality.org

→ In Your Inbox

Get the indispensable guide to the latest on our unequal world, in your inbox every Wednesday.

You can unsubscribe any time. We do not sell or share your information with others.

Click to close

Inequality.org

→ In Your Inbox

Get the indispensable guide to the latest on our unequal world, in your inbox every Wednesday.

You can unsubscribe any time. We do not sell or share your information with others.

Click to close

Inequality.org

→ In Your Inbox

Get the indispensable guide to the latest on our unequal world, in your inbox every Wednesday.

You can unsubscribe any time. We do not sell or share your information with others.

Click to close