Is ‘Neoliberal Feminist’ an Oxymoron?

More women are in positions of power than 50 years ago, but under a fairer system we would have made much more progress on gender equality.

If you want to tell a good tale, the first thing you need to do is set the stage. So let me describe to you the scene of the annual World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. Snow, private jets, champagne. The world’s economic leaders are gathered to discuss “improving the state of the world.”

Into this walks Oxfam International’s Executive Director Winnie Byanyima in full African Power Dress, clutching the one free ticket Oxfam gets every year. She’s there to hold a mirror up to the assembled Davos elites.

In January 2014, she went to present the Oxfam research that just 85 people had the same wealth as the poorest half of humanity. Those 85 individuals could fit in a bus. The poorest half of the global population is comprised of 3.5 billion people.

In 2016, we did the calculations again (although data are not precisely comparable over time) and the number of people who had as much wealth as the bottom half had become 62. And this January we found that only 8 people — all men — were needed to equal the wealth of the poorest half of the planet. In terms of transportation options, we were down to a golf buggy.

World Economic Forum, Manuel Lopez

Winnie Byanyima, the Oxfam International executive director, at the 2017 World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland

Year on year this story is hitting headlines in nearly 100 countries. It has been quoted by International Monetary Fund head Christine Lagarde, President Barack Obama, Chinese President Xi Jinping.

Most people have no idea just how unequal the world is. And so simply reflecting back to the world the state of current wealth inequality has proven very powerful.

And a powerful message is needed. Extreme and growing economic inequality is making it harder to end poverty. It is affecting politics — both due to the influence of money on politics but also because of the polarized societies it creates. It is leading to rising racism and anger. And it is increasingly recognized as a threat to durable and sustainable economies.

But recognizing an issue isn’t the same as doing anything about it. For Oxfam campaigners the last three years have been about asking big questions, like “Why is this research so widely used? What can we learn from that? And what are its limitations in terms of inspiring change?”

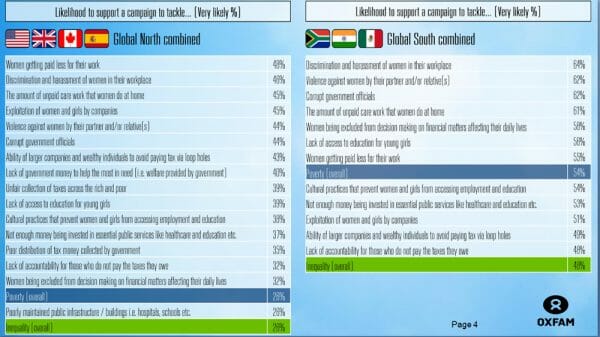

One of our most difficult questions is “How does one campaign against an abstract noun?” And in fact, when people in both the global north and south were asked what topics they’d be “very likely” to campaign on, inequality ranked below many other issues. In both parts of the world, people were more likely to support campaigns on topics like poverty and discrimination and violence against women.

One of the things you might do is to put aside the abstract concept all together. We know that what works as campaigners is specifics, villains, tangible plans for how things could be better. And what specific thing embodies inequality better in today’s world than the tax haven? These are secretive, cynical jurisdictions that contribute little to the economy or society than to ensure a greater return to capital. One estimate is that $7.6 trillion is stashed by rich individuals in tax havens worldwide. They happen to also come with imagery that speaks of luxury and remote secrecy. They are Davos with palm trees. And like many structures there to benefit the richest, tax havens are also incredibly damaging for the poorest.

But what if it’s inequality itself you want to talk to people about? Then you have to understand how people think about inequality, and what values and narratives are holding them back from wanting to address it.

Firstly don’t assume knowledge. Most people have little idea how much inequality exists in society, usually vastly underestimating it, and also having very little concept of where they themselves sit in the distribution. When they do know the truth, they want less inequality. These perceptions have big impacts on their support for action to tackle inequality.

Our campaigning work has also come up against a strong sense that people think inequality is inevitable. This is reinforced by some of the narratives used by political leaders today that see inequality as the inevitable consequence of globalization or technological development. Or they claim that if you want any of the benefits of capitalism you have to accept extreme inequality.

Secondly, action to reduce inequality, such as redistribution, may receive less support because most people around the world consider “your work ethic and ability” to be the top reason why you are rich or poor, and therefore feel that government should not change this too much.

A further challenge is illustrated by the story of colleague was riding on a bus in Mexico the day it was announced that Carlos Slim was the richest man in the world. This Mexican billionaire owes the majority of his wealth to an almost complete monopoly over telecommunications in Mexico, a monopoly that has had a significant negative effect on the economy and almost certainly makes these people pay more for their phones.

Despite this, the news about him being the richest in the world was met with jubilant applause and celebration for the rest of the cross-country bus journey: “He may be a monopolistic oligarch, but at least he’s our monopolistic oligarch.”

So how to respond to these insights? Education is key, but we also have to meet people where they are too. We need to change both hearts and minds.

For instance, when talking about redistribution, talk about the 1%. No one thinks they are in it. You’ll remember that UK Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn did this well in his election campaign, stressing that “95% of people will pay no more tax.” Surely that sounds like me and everyone I know?

Turning to the education approach, Oxfam in Latin America has developed an online calculator tool to show people where they are in the distribution and the real nature of inequality in their country.

And due to launch later in July is Oxfam’s first index of governments’ commitments to reducing inequality. The index will rank over 150 countries by the policy commitments made by governments on tax, public spending, and labor policies. This aims to counter the idea that inequality is inevitable by showing the real range of positions governments have taken.

“Getting an economy that works for most people is seen as a ‘nice to have,’ whilst keeping the overall economy healthy and growing is somehow the main prize. This is all very convenient for those at the top.”

The final problem I want to talk about in relation to campaigning on inequality is the lack of a clear alternative vision. We’re against inequality. But what are we for? What is the vision we want, and what narratives can we use to inspire people it is possible?

Oxfam’s analysis is that both the primacy of economics in policymaking and the inadequacy of that orthodox neoliberal economics are major problems. Just as history belongs to the victors, so economics tends to belong to the winners.

We need to overcome the way the economy is discussed in public policy and media. Think about how the economy is discussed in popular discourse as an independent entity: the economy is healthy or unhealthy, strong or weak. This suggests it needs care over and above the people for whom it should be working.

Where we do ask what the economy is for, the answers seems to be to deliver GDP growth, now and forever — no matter who captures all the growth. The upshot of this being that getting an economy that actually works for most people is seen as a “nice to have,” whilst keeping the overall economy healthy and growing is somehow the main prize. This is all very convenient for those at the top.

So Oxfam is working alongside many others on a similar mission, with community groups around the world to recast some of the popular ways we think and talk about economics.

We refer to the need for a more “human economy,” an economy that explicitly sets out to deliver socially just outcomes for everyone and protects the planet, rather than simply assuming these things will be the outcome of market-based activity.

Essentially, it’s about putting the needs of humanity, and the planet on which we fundamentally rely, first. The role of economics is to serve their needs — not the other way around. It is human outcomes that are fundamentally more important.

We’re at the start of a long journey, with more questions than answers. There is an urgent need to talk about inequality and what to do about it. People from all sides of politics see this — Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump, Theresa May and Jeremy Corbyn. There is a big interest in getting it right, because arguably those who do will define the next decades.

One session of the June 2017 London School of Economics International Inequalities Institute annual conference featured Jee Kim of the Narratives Initiative, Nobel laureate economist Amartya Sen, and Oxfam’s Katy Wright speaking on “Inequalities: Changing the Terms of the Debate.”

by Max Lawson

More women are in positions of power than 50 years ago, but under a fairer system we would have made much more progress on gender equality.

by Jenny Ricks

We will win economic justice when people power becomes stronger than those driving and benefitting from the status quo.

by Manuel Pérez-Rocha

U.S. and Canadian civil society groups are denouncing their own governments’ efforts, driven by the agribusiness industry, to repeal Mexico’s proposed ban on genetically modified corn.

Inequality.org

→ In Your Inbox

Get the indispensable guide to the latest on our unequal world, in your inbox every Wednesday.

You can unsubscribe any time. We do not sell or share your information with others.

Click to close

Inequality.org

→ In Your Inbox

Get the indispensable guide to the latest on our unequal world, in your inbox every Wednesday.

You can unsubscribe any time. We do not sell or share your information with others.

Click to close

Inequality.org

→ In Your Inbox

Get the indispensable guide to the latest on our unequal world, in your inbox every Wednesday.

You can unsubscribe any time. We do not sell or share your information with others.

Click to close

Inequality.org

→ In Your Inbox

Get the indispensable guide to the latest on our unequal world, in your inbox every Wednesday.

You can unsubscribe any time. We do not sell or share your information with others.

Click to close

Inequality.org

→ In Your Inbox

Get the indispensable guide to the latest on our unequal world, in your inbox every Wednesday.

You can unsubscribe any time. We do not sell or share your information with others.

Click to close