Is ‘Neoliberal Feminist’ an Oxymoron?

More women are in positions of power than 50 years ago, but under a fairer system we would have made much more progress on gender equality.

Getty Images

The past year has given us a harsh lesson that nationalist politics offers little when it comes to tackling global crises. Trump may have boasted about closing the border to China, but the Covid-19 virus entered the United States regardless. Meanwhile Trump’s withdrawal from the Paris Accord and climate denialism did nothing to prevent unprecedented wildfires in California nor the drought conditions now afflicting most of the U.S. South and Southwest.

In our era of gated communities and nationalist leaders, it is clear that neither walls, wealth, nor denialism will offer full protection from the global crises we face.

Biden’s election victory, then, offers some hope of the United States recommitting itself to global cooperation. Biden has notably promised to rejoin the UN Paris Climate Accord and the World Health Organization. Yet a closer look at the Democratic Party’s Build Back Better plan suggests that even his administration is dominated by a rather narrow nationalist approach with its conclusion that “the future is made in America, in all of America, by American workers.”

The Biden-Harris plan, if not watered down by corporate or elite interests, does contain important progressive proposals, including raising the minimum wage, investing in unionized good jobs, expanding paid family and sick leave, building a clean energy economy, and closing the racial wealth gap. It is also welcome that they propose “reversing Trump’s tax cuts for corporations and imposing common-sense tax reforms that finally make sure the wealthiest Americans pay their fair share.”

However, if the United States really wants to avoid future pandemics or the consequences of other social and environmental disasters, it will need to address the systemic global fault lines along which these contagions spread.

It is not enough to build a robust response to Covid-19 in the United States, if it is not combined with supporting countries in the Global South to also combat the pandemic and prevent future ones. It is not enough to rebuild the U.S. economy, if the global economy remains weak, hollowed out, and serving only a small rich minority. It is not enough to invest in a clean energy economy within the United States, if there are not resources to support a just climate transition worldwide.

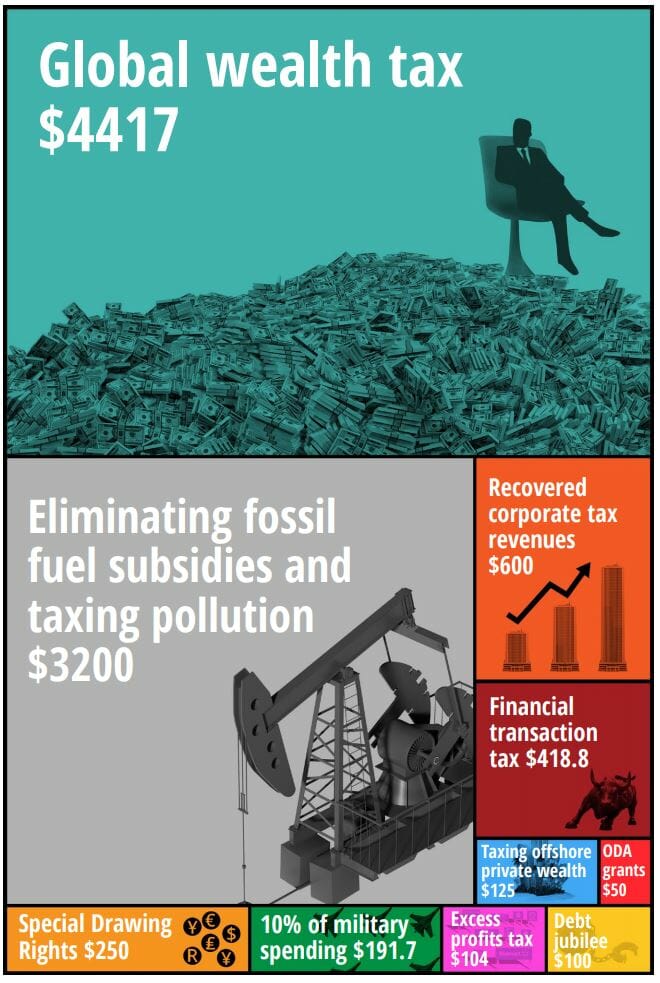

Those opposed to such global action will of course raise the question of how we pay for it, and will insist that the United States has to focus on its own population before looking to the needs of others. Yet a new report by the Transnational Institute shows that there are plenty of ways to raise the global finance needed. Paying for the Pandemic and a Just Transition pulls together ten progressive proposals that could raise $9.4 trillion a year — enough to pay for the pandemic, the Sustainable Development Goals, a just climate transition, and reparations for slavery in the United States. All the proposals are designed to make the elites who have most enriched themselves in past decades pay for the crises we collectively face.

The ten proposals are based on pre-existing policy propositions by international organizations, think tanks, academics, and social movements. They include taxes on billionaires and corporations, shutting down tax havens, removing fossil-fuel subsidies, issuing Special Drawing Rights (a unique IMF currency), and a redirection of 10 percent of global military spending.

For details on sources and methodology, see the new Transnational Institute report Paying for the Pandemic and a Just Transition.

These are proposals that can work globally and support low-income countries that do not have the same capacity as the United States to spend their way out of the crisis. Some of the proposals are easier to implement and even on the conservative end of ambition, while others are more ambitious and only in their embryonic stages of development. But they are all achievable if there is the political will, and even more so if one of the world’s most powerful nations, the United States, puts its political weight behind them.

Covid-19 has already shifted the Overton window of what is considered economically feasible. Actions that were previously deemed extreme such as taking over private hospitals (as happened in Spain) or providing basic income support (as happened in the United States) were enacted quickly in the face of the pandemic. They have shown that policy options that go against the political grain and against corporate interests can be enacted if the issue is considered urgent, necessary, and demanded by the public.

And there is evidence this logic is also influencing the issue of financing. Take the proposal on diverting military spending for example. Some might dismiss it as utopian, but South Korea has announced that it will trim next year’s defense budget by 2 percent ($738 million) and Thailand by 8 percent ($557 million), with the money going instead to a disaster-relief fund and stimulus package respectively. There is every reason why U.S. progressives should demand a similar or bigger reduction in the bloated U.S. military budget.

There is also international precedent on using new taxes to build back better. Indonesia, for example, is planning to implement a new sales tax on digital goods and services to help pay for the pandemic, targeting those who have most profited from the crisis. And political support is building in both the G-24 and the EU for a digital services tax on the tech titans who have made billions from the lockdowns.

This is not to underestimate the resistance these progressive proposals will face. The fossil fuel industry, for example, has used Covid-19 to derail the EU Green Deal, lobbying to win concessions for climate-damaging energy schemes, gain access to bailout funds, and weaken environmental standards. And, the IMF, despite more progressive language, has been pushing countries facing new debt crises into packages that promote austerity.

All of the ten proposals would take money away from a small elite, who will certainly fight their implementation tooth-and-nail. But if we are to have any hope of moving towards a more democratically controlled economy, we cannot shy away from this battle as these powerful groups are largely the cause of many of the world’s social and environmental crises.

Covid-19 provides us with an unmissable opportunity to make a pivot towards a more humane dignified world. As John Feffer of the Institute for Policy Studies argues in a new book, The Pandemic Pivot, “With Covid-19, humanity has been given a second chance. We don’t have to keep trying to muddle through by following the same policies that got us into this mess in the first place, doing the same things over and over again, expecting different results. We can go in a different direction. We can learn from this pandemic in order to pivot toward a more sustainable, more peaceful, and more equitable future”.

In the wake of World War II, a popular movement successfully turned the common experience of a global crisis into an examination of the kind of society people wanted to build. In many countries such as the UK it led to the creation of public health systems and the welfare state. In the United States, it also led to one of the most ambitious global plans, the Marshall Plan, which mobilized $12 billion to help countries in Europe rebuild (the equivalent of $130 billion in 2019).

There were of course other political considerations involved, most notably a desire to counteract the influence of the Soviet Union and cement the U.S. dollar’s status as the global currency. Nevertheless announcing the plan, Secretary of State George Marshall (after whom it was named) said, “It is logical that the United States should do whatever it is able to do to assist in the return of normal economic health to the world, without which there can be no political stability and no assured peace.”

We need a similar internationalist logic today.

by Max Lawson

More women are in positions of power than 50 years ago, but under a fairer system we would have made much more progress on gender equality.

by Jenny Ricks

We will win economic justice when people power becomes stronger than those driving and benefitting from the status quo.

by Manuel Pérez-Rocha

U.S. and Canadian civil society groups are denouncing their own governments’ efforts, driven by the agribusiness industry, to repeal Mexico’s proposed ban on genetically modified corn.

Inequality.org

→ In Your Inbox

Get the indispensable guide to the latest on our unequal world, in your inbox every Wednesday.

You can unsubscribe any time. We do not sell or share your information with others.

Click to close

Inequality.org

→ In Your Inbox

Get the indispensable guide to the latest on our unequal world, in your inbox every Wednesday.

You can unsubscribe any time. We do not sell or share your information with others.

Click to close

Inequality.org

→ In Your Inbox

Get the indispensable guide to the latest on our unequal world, in your inbox every Wednesday.

You can unsubscribe any time. We do not sell or share your information with others.

Click to close

Inequality.org

→ In Your Inbox

Get the indispensable guide to the latest on our unequal world, in your inbox every Wednesday.

You can unsubscribe any time. We do not sell or share your information with others.

Click to close

Inequality.org

→ In Your Inbox

Get the indispensable guide to the latest on our unequal world, in your inbox every Wednesday.

You can unsubscribe any time. We do not sell or share your information with others.

Click to close