Philanthropy

As More Donations Pour into Donor-Advised Funds, Which Charities Will Get Left Behind?

As DAF wealth continues to rocket skyward, organizations that meet acute social needs — such as homeless shelters, food banks, or health clinics — may suffer.

A new study finds that donor-advised funds are changing the nature of charitable giving in the U.S. — both what gets funded, and how.

Donors who do their giving through donor-advised funds, or DAFs, tend to give to different causes than do donors who give directly to operating charities. DAF donors give disproportionately more to educational and religious organizations, and less to human service and healthcare organizations.

And DAFs are increasingly greasing the wheels for donations of highly tax-advantaged assets such as illiquid business partnerships or crypto-assets — assets that are typically available only to the very wealthy, and assets that many working charities can’t absorb.

What are DAFs, and who uses them?

Donor-advised funds, or DAFs, are financial accounts managed by nonprofit organizations, which are called sponsors. Donors can give money to a personal DAF account and take an immediate tax deduction for that gift, since they’re technically giving to a public charity. The sponsor managing the DAF then gives the donor advisory privileges to recommend grants out of the DAF to pretty much whichever qualified charities they want, on pretty much whatever schedule they want.

DAFs are particularly attractive to wealthy donors who itemize their deductions, and who want to get big tax deductions for charitable gifts — especially donors who want to offload appreciated noncash assets like real estate and cryptocurrency without having to pay capital gains taxes on them.

This means that the donors giving to DAFs are, by and large, a different set of people than the typical U.S. donor.

Why should we care how DAF donors give?

Thirty years ago, DAFs were relatively obscure giving vehicles housed in a small set of community foundations, but they have rapidly become central players in charitable giving in the U.S. DAFs now take in more than a quarter of all individual giving each year, and DAF sponsors now represent seven of the ten largest public charities in our country.

Those like us who would like to see more regulation of DAFs have focused a lot of attention on whether DAFs are slowing down the flow of revenue to operating charities — and this attention is warranted.

But we’ve paid relatively little attention so far to how the expansion of DAFs is shifting what types of charities get funded, and the form that funding is taking. I recently was privileged to do a study with Ohio State University accounting professor Brian Mittendorf in which we examined these shifts.

How our study worked

For our analysis, we gathered electronic tax returns for a set of over three thousand donor-advised fund sponsors and hundreds of thousands of working charities. We bumped both the working charities and the DAF grant recipients up against the IRS’s National Taxonomy of Exempt Entities so we could assign each charity to the proper industry sector – environment, healthcare, international relief, and so on.

We then looked at how revenue was flowing through the DAFs. We compared the mix of charities funded by DAF donors to the mix of charities funded by the U.S. population as a whole. And we compared the mix of assets that donors gave to DAFs to the mix of assets that donors gave directly to operating charities.

DAF donors are shifting charitable giving to the causes they prefer — including other DAFs

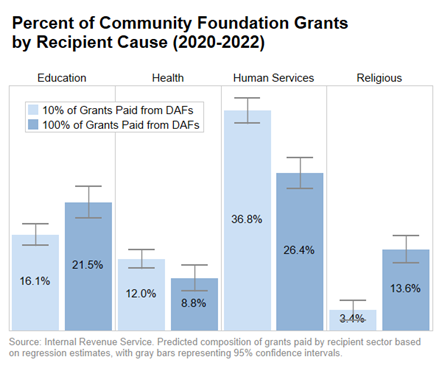

We found that donor-advised funds give to a different mix of organizations than the U.S. population at large. Specifically, DAF donors give disproportionately more to educational and religious organizations, and they do so at the expense of human service and health care organizations.

And we also found that the more of a sponsor’s total grants are made up of DAF grants, the greater these funding differences are.

Our analysis suggests, for example, that a community foundation where all of its grants come from its DAFs would be expected to give 5 percent more of its grants to educational charities and 10 percent more of its grants to religious charities than a community foundation where only 10 percent of its grants come from its DAFs.

And that DAF-heavy community foundation would also be expected to give 10 percent less of its grants to human services organizations, and 3 percent less to healthcare organizations, than the DAF-light community foundation.

We also found that DAF donors give disproportionately more to other DAFs than does the U.S. population at large. This is a significant closed-loop effect that is almost never taken into account in any discussion of the speed of funds flowing out of DAF accounts — but which certainly should be, given that, according to Giving USA 2024, grants going from DAFs to other DAFs now adds up to an estimated $5.6 billion annually.

All of this means that DAF donors tend to fund a different mix of organizations than everyday donors do. As DAFs get more and more popular, the consequence may well be a disproportionate shift of revenue away from organizations focused on acute needs like food, clothing, medical care, and shelter, and towards educational institutions, religious organizations, and other DAFs.

DAFs disproportionately attract noncash gifts — especially those with extra tax advantages for the wealthy.

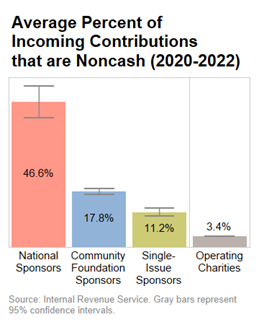

As DAFs grow, they are blowing past working charities. They take in much more in contributions each year, and their assets are piling up much faster. A large part of the reason for this is because DAFs can handle much more complicated and much more highly tax-advantaged donations than working charities can.

In our analysis we found, first of all, that donations to DAFs disproportionately come in the form of noncash assets, usually in the form of publicly-traded stock. Donors get two forms of tax relief when they donate assets like these: they receive an income tax deduction for the value of the asset, and they also avoid paying the capital gains taxes that they would have had to pay if they’d sold the asset instead. Some DAF sponsors use this double benefit as a selling point; for example, Fidelity Charitable, the largest DAF sponsor in the country, calls this “tax smart” giving.

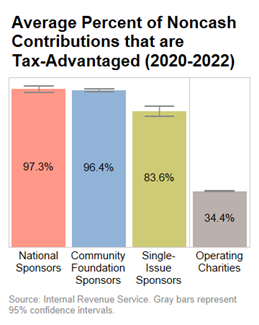

The advantages of DAFs don’t stop there, though. Donations to DAFs don’t just skew towards noncash assets in general; they skew in particular towards the more highly tax-advantaged, complex noncash assets that are only available to the very wealthy, including assets like real estate, artwork, and business partnerships.

These types of contributions set DAFs apart even more. While most large charities aren’t strangers to donations of stock, many aren’t set up to accept these more exclusive noncash assets, which are typically harder to absorb or sell. DAFs make these gifts easy while also letting donors retain a significant degree of control over the assets — a plush combo deal that most operating charities can’t offer.

Our analysis suggests that the more a nonprofit relies on its DAF program, the more its donations come in the form not only of noncash assets, but also of particularly tax-advantaged noncash assets. Our analysis predicts, for example, that if a sponsor has all its assets in DAFs, 25.7 percent more of the contributions to that sponsor would be noncash assets than for a charity with no DAF program. And 88.8 percent more of the contributions to that sponsor would be especially highly tax-advantaged noncash assets.

What this means for us

Much of the attention paid to DAFs in recent years has focused on how much their current structure — particularly their lack of a payout requirement and their close ties to for-profit wealth management firms — works to slow the flow of funds to working charities. But as DAFs continue to expand, the donors that they attract also appear to be changing the nature of charitable giving — both what comes in, and what comes out.

Our study found that DAF donors give very differently than other donors. For one thing, DAF donors make grants to other DAFs at a rapid clip, creating a closed loop of DAF-to-DAF giving. And when compared to the universe of all U.S. donors, DAF donors disproportionately support religious and educational organizations at the expense of human service and health care organizations.

Our study also found that not only are DAFs more apt to receive noncash gifts than are other types of charities, but DAFs are also more apt to receive the sorts of particularly tax-advantaged illiquid noncash gifts that are only available to the very wealthiest donors.

As DAFs account for more charitable revenue, it changes which causes get funded. A shift in support towards the types of charities DAF donors prefer means a shift away from the types of charities everyday donors prefer.

Human service and health care organizations in particular may face substantial financial hardship if they are unable to find a way to tap into the DAF donor population. Educational and religious organizations, on the other hand, may experience a DAF windfall — but could face it in an environment in which urgent needs are even more inadequately addressed.

And taxpayers will pay more to subsidize tax deductions for donations to organizations that are steadily less representative of what they would have chosen.

And as DAFs take in a greater portion of charitable giving, it changes the types of assets that get donated. A shift towards more donations of complex noncash assets means that charities will become more dependent on the wealthy donors who have those assets. Giving may also be more uneven, since gifts are more tied to what is happening in the stock market.

And taxpayers will pay more to subsidize the tax deductions and tax avoidance associated with increasingly tax-advantaged contributions.

Philanthropy is an expression of our collective generosity and human solidarity. But DAF donors are on track to change the landscape of giving, and not necessarily in ways the general public would prefer. We can work to change this, to modernize the rules governing DAFs, to ensure that our charitable system works well for all of us.

Helen Flannery directs research for the Charity Reform Initiative at the Institute for Policy Studies.